What I Liked:

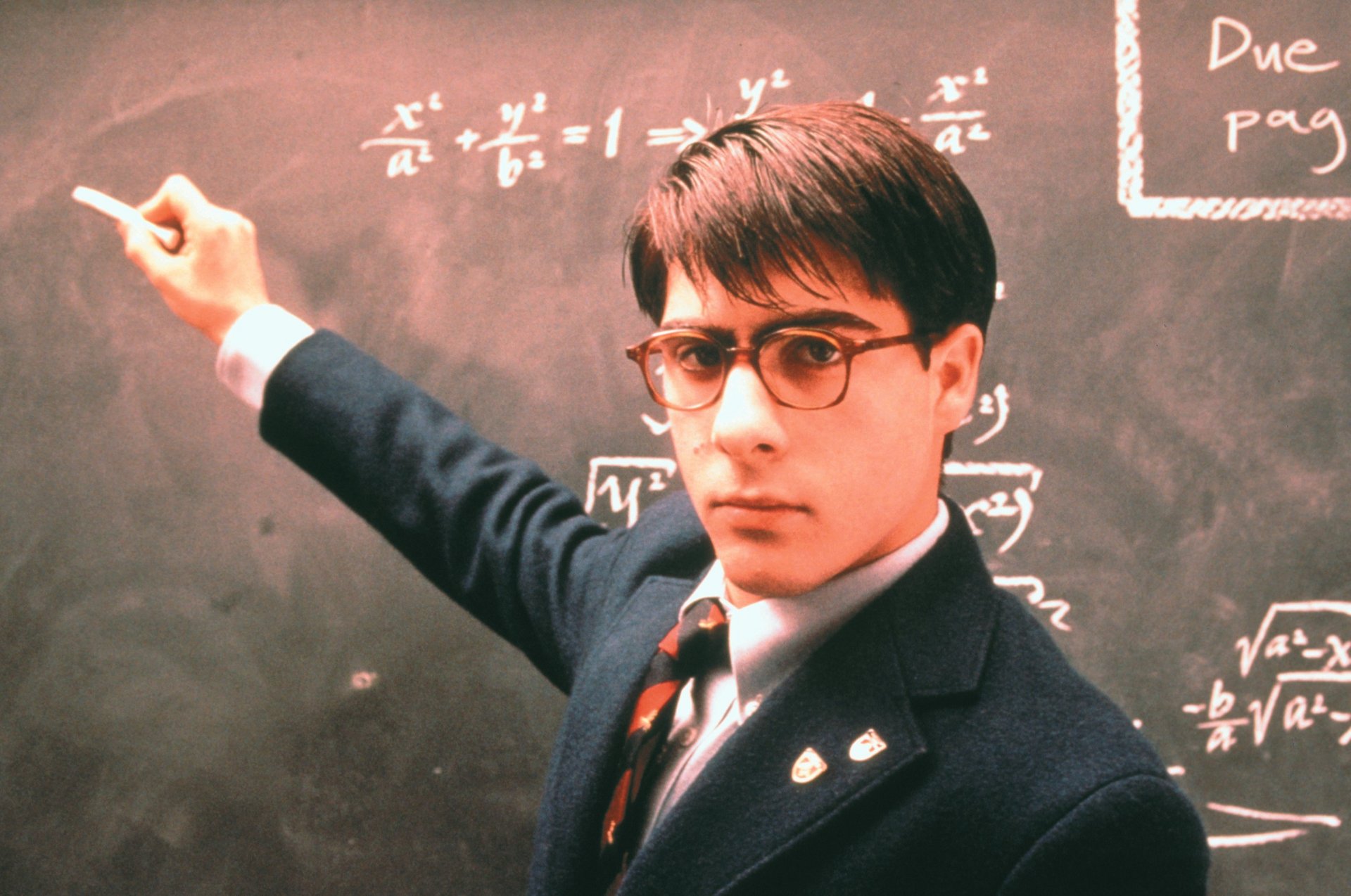

Computer Chess (Andrew Bujalski):

A cosmic comedy disguised as a gimmicky lark that along with the second movie on this list made me as hopeful for the future of independent film as I've ever been. I've written on it already, but a subsequent viewing revealed it to be more tightly structured than I'd thought at first pass, which diminished its moment-to-moment WTF factor (on first viewing it really is an experience of near-constant surprise), but not its thematic richness. It cleverly evokes a hyper-specific milieu and moment in time, but opens generously out to include the present and a sublimely weird future. The difference between it and mumblecore, which its detractors have labeled it as, is that I've never seen a mumblecore movie that made me feel afterward like I'd just a received a warm hug from the Buddha.

The Unspeakable Act (Dan Sallitt):

I find myself slightly embarrassed by my initial praise for The Unspeakable Act, because I characterized both Sallitt and his primary inspiration, Eric Rohmer, as "literary," which, although I didn't mean it pejoratively, I realized after a recent, long-overdue return to Rohmer couldn't be further from the truth. Sallitt and Rohmer alike are after something that only cinema can do, which so many are afraid to do for fear of being labeled "stagy" or "talky," namely give us strong, precise images of people talking with one another. With the image comes mystery. Jackie (Tallie Medel) verbalizes her bizarre emotional life in intricate detail, yet as shot and performed, she maintains (to lift a phrase from an essay I wrote in college which I probably stole from somewhere else) a threshold of unknowability. You know, like a person.

Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Verena Paravel): ....klugklugklugscreeeeeeeeeeeeechkchkckwshhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhaaaaaaamrrrpaaahwoooooooshplunkglogloglogblpblupblupblupchachunkchachunkchachunksplooosh...........................................................................zzzzzzzzzzz.....................rrrreeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeaaaaaaaaaaaaschlipschlipschlipbonnnnnnnnnnnnnghuminahuminaskriiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiitch........caw......caw.......caw....caw...

12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen):

"[A]n arthouse exploitation gift to masochistic guilty liberals hungry for history lessons, some of whom consider any treatment of American slavery by a black filmmaker to be an unprecedented event, thus overlooking Charles Burnett’s far superior Nightjohn."--Jonathan Rosenbaum

Maybe it is functioning that way for that

particular demographic, some of whom doubtless believe a black filmmaker's

never made a movie about slavery before, but what is it doing for the rest of

us? How's it working for black audiences? For conservatives? For some white kid like me who considers himself of the Left, but finds the mixture of guilt and sentimentality with which mainstream liberalism often regards American history

to be finally insufficient for reckoning with its complexity? I don't feel 12

Years a Slave is a particularly enlightening history lesson, per

se, but its attempt to countenance the historical reality of slavery, free

of the usual Hollywood adornments and compromises most treatments of the

subject on film have been marred by, is tremendously moving and politically

substantive, insofar as it doesn't simply present slavery as visceral

you-are-there experience, but examines its toll on the psyche of everyone

involved, a toll which still resonates across our present political landscape.

It's also Steve McQueen's best movie in a walk, I think, because his interest

in bodies under duress has found an ideal subject, one whose political

implications he can't avoid like he did in the otherwise very impressive Hunger (2008),

and whose sheer historical gravity can't brook the overwrought showboating that

made Shame (2011) mildly embarrassing. This has led to

complaints from one quarter that McQueen the formalist has largely gone into

hiding, and complaints from another that when he does appear the results call

too much attention to themselves. I generally lean formalist, but after Shame I

started getting suspicious about McQueen's particular brand of formalism, which

felt there a little too arthouse-gloom-by-numbers, with extended takes that

seem to congratulate themselves on their own daring as they unfold. There are

still extended shots in 12 Years a Slave, but they don't preen;

they're always subordinate to drama and theme. The whipping of Patsey (Lupita

Nyong'o) is captured in one mobile take, but the camerawork is so effortlessly

in tune with the emotional progress of the scene, and the scene itself so

upsetting, that the technique becomes nearly invisible. The lengthy wide shot

of Solomon (Chiwetel Ejiofor) hanging by his neck from a tree, his feet barely

touching the ground, is somewhat more noticeable, but if we recognize the

artist our attention is quickly shifted back to what he's showing us, how

abject human suffering became just another banal detail of plantation life. As

to whether unflinchingly staging and filming acts of

brutality ipso facto constitutes exploitation regardless

of the intentions or artistry of the filmmaker, it's a dicey, complicated

question that deserves to be treated as such. Maybe Burnett's Nightjohn (1996) is the better movie, I wouldn't know, but I'm certain there could not

be a wider gulf between 12 Years a Slave and something like Goodbye Uncle Tom (1971).

A Touch of Sin (Jia Zhangke):

Speaking of dicey, complicated questions: Is it possible to effectively employ action movie tropes to critique capitalism? Action, after all, is the most lucrative and expensive of cinematic genres, each big-budget spectacle a kind of conspicuous production whereby its country of origin flaunts both its literal and economic firepower. A Touch of Sin features some exquisitely framed "badass" tableaux during its scenes of violence that wouldn't be out of place in a spaghetti western or wu xia. These types of images are old hat in Asian cinema, but there's an initial dissonance in seeing them in a movie by Jia, who for the most part works in a social realist mode, albeit an idiosyncratic social realism that mixes fictional and documentary elements. One can look at it cynically and view this as a commercial compromise on his part, yet it's hardly a sell-out. If anything, what Jia does here is defy most of the pleasures of the genre. There's no one hero combating and eventually triumphing over a concrete foe; instead, we have four central characters who are driven by economic circumstance and/or personal proclivity (one of the four is a genuine psychopath) to acts of desperate violence that do nothing to change the system that helped bring them to that point. Jia doesn't order the stories in terms of escalating spectacle: the story with the most extensive and stylized violence comes first; the last story contains the least violence and ends with a sickening thud. Pretty despairing stuff, and blunt as hell (at one point Jia's wife and longtime onscreen muse Zhao Tao is smacked repeatedly in the face with a wad of cash for what feels like a solid minute), but the sheer breadth of territory Jia covers, not only in terms of geography but also the amount of visual information he packs into his laterally-mobile frames, makes for a frequently exhilarating experience.

Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach):

For Greta Gerwig, whose motor functions are totally fascinating. For the enraptured way Noah Baumbach's camera regards her, even when she's peeing off the edge of a subway platform. For the way Adam Driver's hat compliments his Adam's apple. For Baumbach knowing not only which scene to steal from Mauvais Sang (1986), but why he should steal it. For the Truffaut homages being only intermittently annoying. For Hot Chocolate.

Spring Breakers (Harmony Korine):

As I've thought about and revisited Spring Breakers since writing a little thingawhatsit on it back in July, my reservations have mostly fallen away, or at least come to seem a little tiny in comparison to the formidable achievement of this psychotropic dupstep deathdream. I don't think it's the Film of My Generation, but Korine has mapped out a new space for artful filmmaking in a part of Gen Y's cultural experience that's largely been relegated to (and partly conjured into being by) music videos, reality TV and internet porn.

The World's End (Edgar Wright):

Another very enjoyable and sneakily layered comedy from Edgar Wright. Not his most immediately lovable (that would be Shaun of the Dead) or his most inventive (that would be either Hot Fuzz or Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World, depending on how irritated by aspects of the latter I am on a given day), but by far his most emotionally complex to date, with a resonant melancholy underlying the intricate, rapid-fire gags and exhausting man-on-robot melees.

The Strange Little Cat (Ramon Zürcher):

Nothing else this year confounded me quite like this, a disarmingly whimsical exercise in structuralist filmmaking. Some names pop into mind--Tati, Bresson, Akerman, Haneke, Straub/Huillet--but first-timer Zürcher's style is already wholly distinctive, characterized by an emphasis on gestures and objects over legible character psychology and an extensive use of offscreen space, which have the combined effect of making us experience a series of mostly quotidian events as surreal non-sequiturs.

|

| aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaah |

See here. Or, alternately: in a year when everybody from Jia Zhangke to Martin Scorsese (so I hear) to Gore Verbinski (!!) launched broadsides at capitalism, Claire Denis was the nastiest about it, but also the most palpably anguished at how money and the status it confers can enable people to get away with anything. But while it isn't subtle, it also isn't a blunt object; it's mostly sinuous and hushed in the usual Denis mode. And it's another movie this year whose impact would be considerably lessened were it not for Hot Chocolate.

Upstream Color (Shane Carruth):

I tend to prefer my cinematic visionaries more right-brained than Shane Carruth, who probably has a spreadsheet somewhere in which he's mapped out the significance and visual logic of every moment here with mathematic literalness, but credit where it's due. This is a mesmerizing movie, and one of the more narratively and stylistically adventurous works of cinematic speculative fiction in quite some time.

Something in the Air (Olivier Assayas):

See here. This semi-autobiographical account of teen radicalism post-'68 is too honest about the movement's blind spots and failures to reignite anybody's revolutionary fervor, but it doesn't quite fall into defeatism or complacency, either. And, being an Assayas joint, it also has the best soundtrack of the year.

Breaking Bad: "Ozymandias" (Rian Johnson):

In its two-part fifth season, Breaking Bad shifted into a more overtly pulpy register. Walter White having more or less completed his transformation from Mr. Chips to Scarface, this made a degree of structural sense, but it was still a slight comedown from earlier seasons, which struck me as having a bit more going on psychologically. But its antepenultimate episode reached a pitch of tragic intensity that had few equals on the bigger screen, and which I'd really have to grasp to find a precedent for (Buffy's "The Body," maybe?) in the several TV series I hold nearer and dearer to me than this one.

You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet (Alain Resnais):

For about 20 or 30 minutes this was my favorite movie of the year, but once it settled into the play that makes up its bulk, I kept waiting for Resnais to go further, to add another layer of metafictional derring-do, which never quite happens. We mainly get the play, not a bad play but not a great one either, filtered through a couple ingenious pomo devices that eventually exhaust their novelty. But, on balance, another eccentric, lovely gift from one of the youngest 91-year-olds in the world.

To the Wonder (Terrence Malick):

Terry, Terry, what are we to do with you?

You're "image-mad," that gadfly blogger Fred Nietzsche would say;

"Mr. Wackadoodle," esteemed philosopher Jeff Wells has dubbed you.

Cinema Scope's shooting spitballs at you, and that one fellow at TMZ doesn't know who you are.

How have you fallen so?

Must you wander so far from Syd Field into a forest of romantic abstraction?

Must you insistently employ images that remind us imaginatively impoverished capitalist subjects of Cialis commercials?

Must you couch your centuries-old metaphysical queries in banal language that's so easy to feel superior to?

("When people express what is most important to them,

It often comes out in cliches. That doesn't make them laughable;

It's something tender about them. As though in struggling to reach

What's most personal about them they could only

Come up with what's most public."--You, 1973)

What's the deal with your production method now, juggling all these projects?

Are you filming every day? Does Emanuel Lubezki crash on your couch?

It all feels so contingent, Terry. I think that's finally what's bugging people.

Movies aren't supposed to feel contingent,

Like they could be put together a million different ways,

Like clouds that could take any shape but took this particular one just on some cosmic whim.

They're supposed to feel compact and shiny and immediately useful, like a new credit card.

Shape up or ship out, amigo. I won't warn you again.

P.S.: Thank you for realizing Ben Affleck is an axiom.

An incredibly beautiful and mysterious movie of the sort I tend to go for. What holds me back slightly is an overriding sense that Reygadas's image-making is ahead of his meaning-making. The poetic force of his images is sometimes mitigated by the fact that what they appear to be signifying is problematic, when not outright stupid. What's otherwise the movie's single greatest (and gruesomest) shot is one of the worst offenders in this regard. Still, as pure sensory experience it's got a lot going for it.

The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer, Christine Cynn, Anonymous):

I originally rated this much higher, since it nigh-on leveled me, but on reflection I find it hard to fully embrace. Oppenheimer, et al, dive headfirst into the murkiest waters of documentary ethics, and the results are mind-boggling and emotionally devastating, but finally indeterminate. There's also an amorphous bagginess to its construction, even in its shortened theatrical cut, which makes it a more tortuous sit than even a movie on this subject really needs to be.

The Lone Ranger (Gore Verbinski):

See here. But also: the modern blockbuster is an inherently schizoid form, so why not own up to that and see how much weird you can get away with?

Blue is the Warmest Color (Abdellatif Kechiche, French title: La Vie d'Adele)

"For La Jalousie, there were only 5 hours of rushes, and the film runs 1:16. I'm far from Kechiche's 600 hours of rushes for La Vie d'Adèle. His film is better than mine, but is it 100 times better? (laughter) I'm pleased that the French cinema has been saved by La Vie d’Adèle."

--Phillipe Garrel, trans: Richard Brody

See here. Either an admirable failure or a very mixed success. I started my piece on it leaning toward the former, ended it leaning toward the latter. Whatever it ultimately is, may Adele Exarchopoulos go on to conquer the universe.

Fait Accompli: "Episode 1: Caused" (Craig Keller):

Is it sci-fi? Is it mumblecore? Is it a Rivette riff? Is the sound supposed to be doing that? Is this rambling half-impenetrable conversation ever going to end? Am I wasting 90 minutes of my life? But if this is just navel-gazing, why does it have so much of the world in it? Is it some kind of a diary? Is it all about the image, and what digital can do with it? Da fug? Am I just sleep-deprived or is this scene as good as I think it is? Why do I feel like I'm watching Film Socialisme (2010) all of a sudden? Is this the future? When's Episode 2 coming out?

Gravity (Alfonso Cuaron):

Asia Argento's Vinebox (Asia Argento):

My favorite recent source of new media ephemera. The amphetaminic cutting suggests a life lived headlong. Visual expresso. Highlights: "It hurts so bad," "I want you with Abel," "I got a hole in my lungs in my muthafuckin lungs," "Get us a whale shark at once."

Something I Didn't Like:

Only God Forgives (Nicolas Winding Refn)

Dissed it here. Refn isn't quite top offender in the case of The Post-Tarantino Fanboy Auteur as Evolutionary Dead End, but one more like this and he'll dethrone Robert Rodriguez.

Best Things I Saw This Year, Period:

Floating Clouds (Naruse, 1955)

L'Argent (Bresson, 1983)

Zero for Conduct (Vigo, 1933)

Hi, Mom! (De Palma, 1970)

David Holzman's Diary (McBride, 1967)

Dead Ringers (Cronenberg, 1988)

The Silence (Bergman, 1963)

Rome, Open City (Rossellini, 1945)

Menilmontant (Kirsanoff, 1926)

Culloden (Watkins, 1964)

The Exterminating Angel (Bunuel, 1962)

Trust (Hartley, 1990)

Rebel Without a Cause (Ray, 1955)

Very Nice, Very Nice (Lipsett, 1961)

L'Amour Existe (Pialat, 1960)

A Nos Amours (Pialat, 1983)

Punishment Park (Watkins, 1970)

Regular Lovers (Garrel, 2005)

Gang of Four (Rivette, 1988)

The Devil Probably (Bresson, 1977)

Out 1: Noli Me Tangere (Rivette, 1971)

Night at the Crossroads (Renoir, 1932)

Edvard Munch (Watkins, 1974)

Noroit (Rivette, 1976)

Journey to Italy (Rossellini, 1954)

Antoine and Colette (Truffaut, 1962)

Barres (Moullet, 1984)

Out 1: Spectre (Rivette, 1974)

The Servant (Losey, 1963)

En Rachachant (Straub/Huillet, 1983)

Nenette and Boni (Denis, 1996)

Lucifer Rising (Anger, 1972)

The Sleeping Beauty (Breillat, 2010)

Dazed and Confused (Linklater, 1993)

Nadja in Paris (Rohmer, 1964)

Sisters of the Gion (Mizoguchi, 1936)

The Ravishing of Frank N. Stein (Schwizgebel, 1983)

Distant Voices, Still Lives (Davies, 1988)

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Hawks, 1953)

Scarface (Hawks, 1932)

Deep End (Skolimowski, 1970)

La Notte (Antonioni, 1961)

Corridor (Lawder, 1970)

Titicut Follies (Wiseman, 1967)

High School (Wiseman, 1968)

Hahaha (Hong, 2010)

Claire's Knee (Rohmer, 1970)

Love in the Afternoon (Rohmer, 1972)

The Aviator's Wife (Rohmer, 1981)

The Green Ray (Rohmer, 1986)

Before Sunset (Linklater, 2004)

Modern Romance (Brooks, 1981)

A Town of Love and Hope (Oshima, 1959)

Night and Fog in Japan (Oshima, 1960)

Boy (Oshima, 1969)

Eros Plus Massacre (Yoshida, 1969)

Asia Argento's Vinebox (Asia Argento):

My favorite recent source of new media ephemera. The amphetaminic cutting suggests a life lived headlong. Visual expresso. Highlights: "It hurts so bad," "I want you with Abel," "I got a hole in my lungs in my muthafuckin lungs," "Get us a whale shark at once."

Something I Didn't Like:

Only God Forgives (Nicolas Winding Refn)

Dissed it here. Refn isn't quite top offender in the case of The Post-Tarantino Fanboy Auteur as Evolutionary Dead End, but one more like this and he'll dethrone Robert Rodriguez.

Best Things I Saw This Year, Period:

Floating Clouds (Naruse, 1955)

L'Argent (Bresson, 1983)

Zero for Conduct (Vigo, 1933)

Hi, Mom! (De Palma, 1970)

David Holzman's Diary (McBride, 1967)

Dead Ringers (Cronenberg, 1988)

The Silence (Bergman, 1963)

Rome, Open City (Rossellini, 1945)

Menilmontant (Kirsanoff, 1926)

Culloden (Watkins, 1964)

The Exterminating Angel (Bunuel, 1962)

Trust (Hartley, 1990)

Rebel Without a Cause (Ray, 1955)

Very Nice, Very Nice (Lipsett, 1961)

L'Amour Existe (Pialat, 1960)

A Nos Amours (Pialat, 1983)

Punishment Park (Watkins, 1970)

Regular Lovers (Garrel, 2005)

Gang of Four (Rivette, 1988)

The Devil Probably (Bresson, 1977)

Out 1: Noli Me Tangere (Rivette, 1971)

Night at the Crossroads (Renoir, 1932)

Edvard Munch (Watkins, 1974)

Noroit (Rivette, 1976)

Journey to Italy (Rossellini, 1954)

Antoine and Colette (Truffaut, 1962)

Barres (Moullet, 1984)

Out 1: Spectre (Rivette, 1974)

The Servant (Losey, 1963)

En Rachachant (Straub/Huillet, 1983)

Nenette and Boni (Denis, 1996)

Lucifer Rising (Anger, 1972)

The Sleeping Beauty (Breillat, 2010)

Dazed and Confused (Linklater, 1993)

Nadja in Paris (Rohmer, 1964)

Sisters of the Gion (Mizoguchi, 1936)

The Ravishing of Frank N. Stein (Schwizgebel, 1983)

Distant Voices, Still Lives (Davies, 1988)

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Hawks, 1953)

Scarface (Hawks, 1932)

Deep End (Skolimowski, 1970)

La Notte (Antonioni, 1961)

Corridor (Lawder, 1970)

Titicut Follies (Wiseman, 1967)

High School (Wiseman, 1968)

Hahaha (Hong, 2010)

Claire's Knee (Rohmer, 1970)

Love in the Afternoon (Rohmer, 1972)

The Aviator's Wife (Rohmer, 1981)

The Green Ray (Rohmer, 1986)

Before Sunset (Linklater, 2004)

Modern Romance (Brooks, 1981)

A Town of Love and Hope (Oshima, 1959)

Night and Fog in Japan (Oshima, 1960)

Boy (Oshima, 1969)

Eros Plus Massacre (Yoshida, 1969)