Man with a Movie Camera: Propaganda, Modernity,

and Cinema as Truth-Medium

Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) is usually classified as a documentary, but

a typical documentary presents us with verbal and visual information about a particular subject, usually arranged in a comprehensible narrative. Instead, Vertov’s film attempts to

encompass every conceivable aspect of modern life in just a little over an

hour, a kind of Ulysses of the

cinema. This totalizing ambition could be said to consist in practice of a trio

of overlapping assertions of power: the power of Soviet Russia in the 1920s,

the power of modernity in general, and the power of cinema to capture both in

concentrated, intensified form.

Like many films of the Montage

movement, one of the film’s intended functions was as propaganda for the state.

Vertov showcases the Soviet nation’s industrial, technological, social, and

economic vitality. Its cities, its public services, its modes of transport, its

markets, its factories, and its entertainments are all seen serving the needs

of the Russian people with mechanistic speed and efficiency. The people, too,

are shown to be going about labor and leisure with spirit and vigor, and rarely

without a smile. The vision of Soviet life the film presents us with is highly idealized. Even the one funeral we see is a parade. There are a small handful of

sobering moments, like the sight of a disheveled and possibly homeless young

man sleeping outside and the desolate faces of a couple filing for divorce. But

even those examples are mitigated by our later seeing the young man (or a young

man closely resembling him) grinning and laughing at the camera, and the sense

we get in the latter scene that having a nonjudgmental legal infrastructure in

place to handle divorces is necessary to the functioning of any progressive

modern society. Not only does Vertov take only a passing glance at the

underside of such a society, but the city that seems to the spectator one

unified area (to the extent that a film so editorially disjunctive and

nonlinear can be said to construct a coherent space) is actually a composite of

several different cities, a patchwork of the best of Russia. The film served to

flatter Russian spectators that their country was at the forefront of the 20th

century, and emphatically announce to the world that it was competing with a nation of great socioeconomic muscularity and technical

ingenuity—that the communist experiment was succeeding grandly.

At the same time, there is nothing especially politically didactic about the film. There are no intertitles contextualizing the

images Vertov presents or exhorting the audience to feel anything in particular

about them. There is no fictional narrative and no conventional

identification. We witness relatable human moments throughout, many of which

are affecting and amusing, but quickly we’re on to the next attraction. There

are no references to political struggles, and only occasionally in the flux of

rapid-fire images are we reminded that we’re looking at the Soviet Union and

not some generic thriving modern metropolis. This is one of the things that

distinguishes Vertov’s project from that of Sergei Eisenstein. Eisenstein’s

work spins fictional narratives from historical events; though in films like Strike (1925) and Battleship Potemkin (1925) he eschews protagonists, he applies the

protagonist/antagonist polarity onto broader social forces, and makes the

conflict between the two as emotionally galvanic as possible for the spectator

by deploying disjunctive editing techniques and shocking imagery, like animal

slaughter and the deaths of children. Vertov thought Eisenstein’s work a

half-measure, more like conventional narrative cinema derived from the

capitalist West and given a revolutionary tinge rather than a true

top-to-bottom revolution of the form. Eisenstein’s films are still appreciated

for their technical skill and emotional impact, but their politics are very

much tied to their era and seem naïve and simplistic now. By keeping its

politics implicit, Vertov’s film serves (and served even in its original

context) a broader function than propaganda—it’s a visual essay on the many

forms of modernity. The rush of a train, the bustle of an intersection

crisscrossed by trolleys, the whir and stutter of a projector, the frenzy of a

cigarette assembly line, the glide of a boat into port, the cascade of water

over a dam, the gaudy gaze of a storefront mannequin, a goalie diving for a

soccer ball, a baby emerging from its mother’s womb, a white mouse crawling from

under an overturned cup during a magic show, the mud-caked breasts of

exfoliating bathers, the face of a child in a transport of joy—the film is a

document or index of these and many other sensations, movements, and textures,

arranged for us in intricate, fast-shuffling patterns dictated by themes and

visual rhymes. The rapid-fire barrage of images is exhilarating and functions

as a kind of visual praise-song to modernity, which in its relentless

affirmation and seeming comprehensiveness can be likened to one of Walt

Whitman’s more expansive, list-heavy poems.

But unlike Whitman, Vertov—true to

both his Marxist-Leninist and Futurist bona fides--is relentlessly materialist,

omitting from his vision any kind of recognizable spirituality (to my

recollection, the closest we get to the conventionally spiritual is a glimpse

of a church) and focusing instead on physical mechanics, the spectacle and visceral

force of objects and bodies in motion. As exciting as this is to watch, one

might find something slightly uneasy in Vertov’s folding of the human processes

of birth, betrothal, and death into this mechanistic vision. The sequence that

crosscuts mothers in labor, wedding ceremonies, and funeral processions puts

one in mind of the assembly line sequences. Should (the good American humanist

within us might ask) this connection between life cycles and mass production be

so easily drawn? Aren’t human beings of greater substance than their

technology?

But the film itself throws a lifeline to the

humanist, in the form of cinema, personified in the figure of the title. Though

subject to the same attention to mechanics as everything else in Vertov’s

vision of modernity, cinema is the wellspring of the film’s humanity. The

cinema is both an eminent example of mechanized modernity and a means of (re-)introducing

a humane sense of play and poetry into same. In addition to an inventory of possible

subjects for cinema, the film is also an inventory of cinema’s stylistic

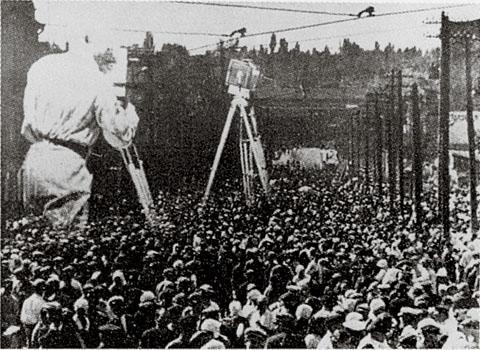

possibilities: rapid cutting, canted and skewed camera angles, slow, fast, and reverse motion, freeze frames, and seemingly dozens more. In the film’s most surreal

moments, mirror effects fold buildings in two, superimpositions make the

cameraman appear to tower over the city and shrink to fill a glass of beer, and

with stop motion animation a camera, tripod and carrying case become sentient

beings, clowning for both us and on-camera spectators.

The film’s extreme reflexivity locates

it as a precursor to postmodernism, but the film is philosophically more

modernist than postmodernist, in that there’s never any doubt that underneath

the layers of reflexivity and cinematographic and editorial tricks we are

seeing the real world, within a constructed text to be sure, but one

constructed largely of images whose reality might be mediated but is not

mitigated, mutilated, or destroyed by the apparatus of cinema. In fact, Vertov

saw his cinema as a means of apprehending kino-pravda

(film truth), an augmentation and extension of the eye rather than a deception

of it, the tricks his camera performs less a demonstration of reality-defying

artifice than of what new ways of seeing the world had been opened up by the

advent of cinema. One element of his theory which resonates with the notion

floated above of the cameraman as the primary ambassador of the human in the

film's mechanized world is that of the truth of the encounter, the idea that there is something inherently truthful about the negotiation that takes

place between the filmmaker and the filmed subject, as if putting an image of a

person to celluloid is akin to capturing their (essential? objective? factual?)

self in motion. Man with a Movie Camera

may sideline the spiritual, but it cannot escape metaphysics. Vertov’s method

was undergirded by some grand assumptions about truth and being, albeit couched

in terms that were half-scientific and half-reportorial. Kino-pravda has its descendants in the Christianity-inflected criticism of Andre Bazin, Jean-Luc Godard’s theoretical interrogations of image

and sound, the fetishism of authenticity by such movements as cinema-verite and

Dogme 95, and Werner Herzog’s theory of “ecstatic truth.”

But despite all the heavy

theoretical baggage that attends Man

with a Movie Camera, it is fundamentally an advertisement—for the culture that

produced it, for the modern world, and for cinema itself. And it may be the

greatest advertisement ever made.

No comments:

Post a Comment